In this final part of the 2008 Financial Crisis Part 3 series,

we will explore the greed that fuelled the biggest crash to date and

how it nearly brought down the entire interconnected financial system.

If you haven’t read 2008 Financial Crisis Part 1, CLICK HERE, and for Part 2, CLICK HERE.

2008 Financial Crisis: CSE

As discussed in 2008 Financial Crisis Part 2, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

allowed investment banks to set their own leverage ratios under the

Consolidated Supervised Entities (CSE) policy.

To me, it seems the SEC didn’t give this policy any proper thought whatsoever.

This policy granted significant power to five major investment banks.

With this power, greed overtook their judgment.

Without considering the consequences,

they began taking on so much debt that their reserves couldn’t even come close

to covering their losses if their holdings went sour.

In essence, even a beginner trader can tell there was zero risk management.

The 5 Investment Banks

1. Morgan Stanley

2. Lehman Brothers

3. Goldman Sachs

4. Bear Stearns

5. Merrill Lynch

Let’s examine how each of these banks increased

their leverage ratios from the time the policy was issued in 2004 until 2007:

Morgan Stanley

• 2004 Leverage Ratio: 24:1

• 2007 Leverage Ratio: 33:1

• Increase: Approximately 38%

Lehman Brothers

• 2004 Leverage Ratio: 23:1

• 2007 Leverage Ratio: 31:1

• Increase: Approximately 35%

Goldman Sachs

• 2004 Leverage Ratio: 22:1

• 2007 Leverage Ratio: 26:1

• Increase: Approximately 18%

Bear Stearns

• 2004 Leverage Ratio: 27:1

• 2007 Leverage Ratio: 33:1

• Increase: Approximately 22%

2008 Financial Crisis Part 3: How Leverage Ratios Work

To explain how leverage works, let’s use Bear Stearns’ leverage ratio from 2004 as an example.

First, you need to understand that a leverage ratio is the total assets divided by shareholders’ equity.

For Bear Stearns, the 27:1 ratio meant that the firm held $27 in assets (or liabilities, including borrowed funds)

for every $1 of equity. In other words, for every $1 of equity, Bear Stearns borrowed

an additional $26, making up the $27 in total assets.

Here’s a step-by-step example:

• Suppose Bear Stearns had $1 billion in equity.

• This would translate to $27 billion in assets.

• If the bank experienced a market loss of just 3.7% of total assets,

it would eliminate its equity reserves completely.

Isn’t that insane?

2008 Financial Crisis Part 3: The Beginning of Horror

In June 2004, the Federal Reserve (the Fed),

influenced by the U.S. government, began increasing interest rates.

Let’s revisit the context: In prior years, interest rates were cut to 1%

to prevent the U.S. economy from falling into a recession following the 9/11 attacks and the dot-com bubble crash.

Fast forward to 2004, and the Fed initiated a tightening cycle, gradually increasing rates.

• June 30, 2004: Rates rose from 1% to 1.25%.

• September 21, 2004: Rates increased to 1.75%.

• The hikes continued steadily, and by mid-2006, rates had soared to a whopping 5.25%.

This sharp increase in interest rates set the started one of the most horrific financial crises in modern history.

What Did It Mean to Home Lenders?

Before we address the horror about to unfold, we need to understand this: At the time, banks had issued a lot of loans based on the 1% rates.

Now that rates had jumped to 5.25%, this simply meant that many homeowners were about to default.

(Rising rates + low-income subprime borrowers = disaster.)

For many homeowners with low credit scores,

paying little to nothing in interest suddenly became unsustainable. For example:

• Old payment: $640

• New payment: $1,100

Home Prices Falling

Home prices began crashing due to widespread defaults (foreclosures).

In 2007 alone, approximately 1.3 million properties were foreclosed

upon, according to NBC News, further escalating the housing market crash.

2008 Financial Crisis: New Century Bankruptcy

Investors started witnessing the horrors that were about to unfold. In early 2007,

New Century Financial Corporation, one of the largest subprime mortgage lenders in the U.S., filed

for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on March 12, 2007.

This shook the market and contributed to a loss of confidence in the housing sector.

Investors scrambled to sell any investments tied to mortgage loans.

Interconnected Global System

The collapse of New Century Financial Corp

and subprime mortgages spread across the global system.

For example, after New Century Financial Corp filed for bankruptcy,

Northern Rock, a UK bank heavily exposed to the subprime mortgage market,

faced a bank run on September 14, 2007. This was the first bank run in over 100 years in the UK.

The UK government quickly intervened,

bailing out and later nationalizing the bank to prevent further financial distress.

The Madness Continues: Financial Crisis

In March 2008, the horror continued as Bear Stearns became the next casualty.

According to CNN Business, Bear Stearns, the fifth-largest bank in the U.S.,

had a market cap of approximately $15 billion before the crash.

Excessive leverage led to its downfall.

Bear Stearns was acquired by JPMorgan for just $2 per share,

with a $29 billion government bailout to address the liquidity crisis.

2008 Financial Crisis: Lehman Brothers Bankruptcy

According to the Corporate Finance Institute, Lehman Brothers,

the fourth-largest investment bank, had a market cap of $60 billion

and was heavily invested in mortgage-backed securities and subprime loans.

Facing bankruptcy, Lehman Brothers attempted to raise capital but failed.

Unlike Bear Stearns, the U.S. government did not bail out Lehman Brothers,

as main street opposed using taxpayer money to rescue Wall Street.

The UK government also blocked Barclays from purchasing Lehman Brothers.

On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy.

Investors Lost Everything; Big Banks Made Billions

Banks like Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs began betting

against the same mortgage securities they were selling,

making hundreds of millions of dollars while investors lost everything.

2008 Financial Crisis: Recession

During this time of uncertainty, banks stopped lending

to each other due to shaken investor confidence.

This lack of credit led to massive job losses,

With the U.S. economy on the brink of a depression,

hundreds of thousands of jobs were being lost each month.

Small businesses shut down, and over 2.3 million foreclosures occurred in 2008 alone.

The stock market crash wiped out trillions in retirement savings, putting financial strain on the middle class.

AIG Bailout

The U.S. government bailed out American International Group (AIG) because it was deemed “too big to fail.”

AIG’s collapse would have had disastrous to the global economy

consequences for banks and pension funds insured by it.

The bailout totalled approximately $182 billion, according to the U.S. Department of the Treasury..

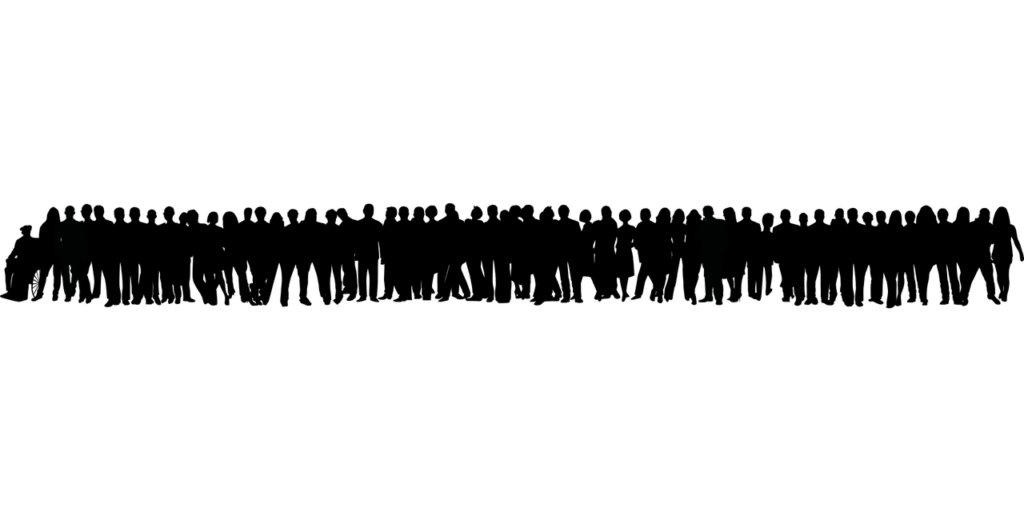

Public Outrage

The Federal Reserve printed massive amounts of money and flooded the system,

which ultimately had to be repaid through taxes.

Hard-working civilians who had no role in causing the crisis bore the burden,

while big banks grew even richer.

Some argue that allowing these institutions

to collapse would have led to a Great Depression-like scenario,

Others believe the intervention only encouraged corruption and greed.

Quantitative Easing: Q4 2008

In November 2008, the Federal Reserve announced a quantitative easing program to combat the crisis.

They purchased $600 billion in mortgage-backed securities

and government debt to stabilize the housing market.

How Did This Affect Main Street?

The 2008 financial crisis led to massive job cuts and small business closures.

Over 2.3 million foreclosures occurred in 2008,

and the stock market crash wiped out middle-class retirement savings.

2008 Financial Crisis Part 3: Conclusion

The 2008 Financial Crisis demonstrated the devastating consequences of greed,

too much risk-taking, and a lack of effective due diligence .

From the SEC’s misguided policies to large leverage volumes,

these factors created a catastrophe that spread globally.

Millions suffered due to foreclosures,

unemployment, and lost savings.

While the intervention may have stopped the bleeding by preventing

the country from going into a depression,

it also left long-term challenges to address,

the aftermath left many questioning whether the benefits outweighed the costs.

As we close this chapter of financial history, it’s crucial to carry these lessons forward.

In future articles, I’ll explore ways to hedge

against financial crises and equip you with tools to navigate uncertainty.

Stay tuned to learn how to protect your wealth and prepare

for potential challenges on the horizon.